- HOME

- TRENDING

- PEOPLE

- COMMUNITY

- LIFESTYLE

- OUR PUBLICATIONSOUR PUBLICATIONS

- MASALA RECOMMENDS

- MASALAWEDS

In the year 1947, Christian Dior made his graceful debut in the fashion world, Tweety Bird and Sylvester first appeared together in the Academy Award-winning Tweetie Pie, and a bottle of Coca-Cola would cost you five cents. While pop culture delivered an enriching experience, the more devastating geopolitical landscape took a turn for the worse, where an 18 year-old Sikh boy found himself petrified, hiding from gunmen in his neighbour’s basement – not knowing his world was about to change forever as Viscount Lord Louis Mountbatten announced the creation of Pakistan.

This is the story of Kartar Singh Narang, who grew up in Akalgarh, a small village in Punjab – a province of what was then called British India, now Pakistan. He lived a peaceful, happy childhood in the area where his family had been settled for generations. When the British government announced liberation, they determined that the provinces with a Muslim majority would become Pakistan and the rest would become India. The situation in Punjab was not as clear-cut. A mixture of religions coexisted there. The new border was thus created through the middle of Punjab – splitting it in two. Thousands of people on both sides were displaced because, like Kartar, they happened to be of ‘the wrong religion for their side of the border’. Religious riots ensued, and many lost their lives. Kartar was amongst those who survived but were forced to flee and embrace life as a refugee.

Today, Kartar lives a comfortable life with his wife in his house in Sukhumvit and is the co-owner of a flourishing business in Thailand. “I never thought I would be a businessman,” he laughs. “My father, he was a doctor. My elder brother was also a doctor. Our family was always serving the government. I was going to be an engineer or a doctor.”

In the summer of 1947, Kartar was back in Akalgarh for his university holidays. He had one semester remaining to complete his science degree at the Guru Nanak Khalsa College in the neighbouring city of Gujranwala. “I didn’t finish my degree. There were so many riots, even before the partition. They had to close the college.” The situation escalated so severely that one of the family’s Muslim friends implored them to stop venturing outside their house. “We were staying in the house – just like house arrest,” Kartar recalls.

Eventually, they were left with no choice but to evacuate because word had spread that theirs was a non-Muslim household. That is how, that day in history, the 18-year-old Sikh boy found himself in his neighbour’s basement fearing for his life – falling asleep to the sound of gunshots. “I was very, very scared. We were lucky we left the house because, that very night, demonstrators came to our home. They wanted to kill us but they could not find us. They broke down the door and took all our belongings instead.”

The Indian military arrived within the next few days and started the evacuation process. All the non-Muslims living in what had become Pakistan were rounded up and taken to relief camps. Kartar’s family slept on mattresses in the classrooms of his old high school for 14 days before getting word that there would be convoys taking people across the border. The only problem was that the trip would cost money – their only possessions were the clothes on their back. Nevertheless, the family made their way to the bus and took seats.

“They kept asking us for money and tried repeatedly to force us off the bus when we told them we didn’t have any. There was no way we were moving. We just sat there. Eventually, they had to take us,” reminisces Kartar with a smile.

He looks around the living room. A Japanese doll on the mantelpiece; a showpiece with an illustration of Canada on the table; and a framed painting of a pharaoh on a piece of papyrus hangs next to a picture of the Golden Temple on the beige wall, all mementos of his travels. “I am very lucky to be where I am today, no doubt. I remember when we first arrived in India, we slept on footpaths in Amritsar until my brother found us in the Golden Temple,” he gestures at a photograph.

Kartar’s brother Avtar was a veterinarian who had elected to live in what became India long before the partition. When he heard about the convoys bringing people to Amritsar, he made his way there at once to search for his family. They were reunited at the Golden Temple, the most sacred Sikh shrine in the world. The family then made their way to Avtar’s house in a town called Ferozpur but within 10 days, severe floods hit and dictated another evacuation into the unknown.

Over the next three and a half months, Kartar and his family tried to rebuild their lives in the cities of Moga, Ludhiana and New Delhi. In Moga, the government allotted them a house belonging to a Muslim family who had fled to Pakistan – it was burnt to a crisp. The month in Ludhiana was spent living with family-friends.

Kartar tells the story of New Delhi with a twinkle in his eye. “We saw that there was a big vacant house so we jumped and rushed to the door and just opened it. That house was government property and was allotted to a Muslim resident but he had moved to Pakistan.” During the two months they spent squatting in the house, the family established contact with their relatives in Bangkok – the city where Kartar’s two sisters were married and his fiancée Harbans and her family were living. Kartar and Harbans had never met but his brother in-law and her father organised the paperwork and invited his family to Thailand.

“At the time, we were thinking that maybe the life here would be better than the life we had in India. But when we came here, we had a small house; we lived with my brother-in-law for nearly 10 years. There were 11 of us on two floors that were 6 meters long and 4 metres wide each.”

Kartar got a job as an accountant. Alongside, he started working on his own by taking samples of fabric from shop to shop, trying to sell it for a profit. His brother-in-law was doing the same. They decided to form a partnership and purchased a shop in Sampheng where they sold textiles. A few years later, they made the crossover to plastic and the rest, as they say, is history.

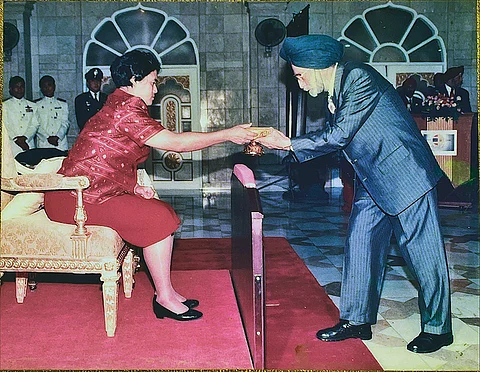

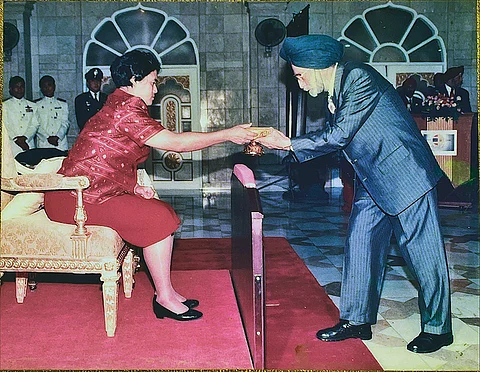

Kartar plays with the orange bracelet on his wrist – ‘long live the king’ it says. Behind him is a framed photograph of himself with HRH Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, taken when he donated to her charity in 1993.

“At first, I didn’t like it here so much but I do now. We are established here, it’s nice. It’s funny, I have lived here for nearly 60 years but don’t have a Thai passport. I applied for one many years ago but wasn’t given it. I definitely think of myself as Thai though. Not 100% but 70% Thai. I can read, write, and speak Thai fluently.”

Like Kartar, thousands of others from the subcontinent have found their refuge in Thailand. As time flows and new generations emerge, these memories—like ink slowly fading on an ancient page—risk being lost to history. It is through the sharing of these stories that we honour the struggles of the past, recognising the sacrifices that have paved the way for the lives we lead today.

This article was written by Kartar Singh Narang’s granddaughter Kiran Narang in 2007. His story was captured through a series of recorded interviews.

Kartar Singh Narang passed away on 7 October 2024 at the age of 96 years old. His family believes it is important to share his story because so many in our community, and those reading this magazine, may have similar stories that remain undocumented. By sharing his journey, we hope to honour our collective history and ensure these experiences are never forgotten.