- HOME

- TRENDING

- PEOPLE

- COMMUNITY

- LIFESTYLE

- OUR PUBLICATIONSOUR PUBLICATIONS

- MASALA RECOMMENDS

- MASALAWEDS

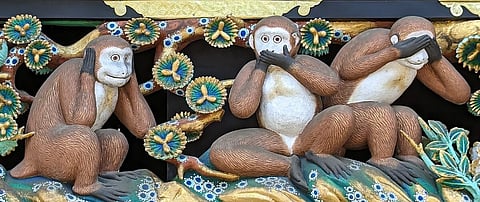

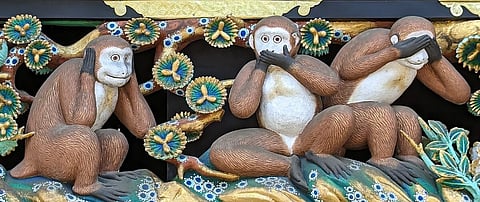

I had absolutely no idea that the three wise monkeys—one covering his eyes, one his ears, and the third, his mouth; the pictorial maxim embodying the proverbial principle, ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’, was a cultural symbol originating at the Tōshō-gū shrine in Nikkō, Japan.

The primates picturing Confucius’ Code of Conduct are on the second of the eight 17th-century panels, carved over the doorway of the stable of the Shinto shrine. Incorporating the seemingly unconnected native macaque monkeys into the code was instigated by a simple play on words.

In the classical Nihon-go, Japanese language, the suffix -zu or –zaru is commonly used as an auxiliary to negate a verb or express its opposite meaning. It can also be translated as ‘un-‘, as in unstoppable or ‘without’, and of course, as ‘not’. Interestingly, this -zu or -zaru happens to sound just like another, different -zaru; the voiced form of saru, meaning monkey in Japanese.

And thus, came about the monikers for these snow monkeys with brownish grey fur, pinkish-red faces, and short tails:

We were introduced to the idiom by Patrick Lafcadio Hearn, a Greek-born Irishman who went to Japan in 1890, at the age of 40, as a journalist, where he married, became a citizen, and adopted the name of Yakumo Koisumi, and where he’d remain for the rest of his life.

Already a prolific writer in English, Greek, and French, Hearn spent his years teaching, and with great insight, he wrote and translated and acquainted the outside world with the hitherto largely unfamiliar Japanese culture and literature, including the maxim which we refer to as the ‘three mystic apes’ or Sambiki Saru.

But as with anything, with time, the traditional Buddhist interpretation of the proverb as a cautionary to avoid evil thoughts and deeds has diverged to mean ‘turning a blind eye to indecent, improper, or offensive behaviour.’

Which translated means, don’t get involved with what doesn’t affect you directly. Bluntly put, look the other way, even when you see someone being victimised; it’s cooler and easier to be a passive spectator and go about doing whatever it is you were about to do, however important or be it as trivial, going to pick up a sub sandwich.

Why bother to deviate; look away and avoid getting yourself in a fix, when, it’s anyway, it’s none of your business. The person or persons, whether the victim(s) or the perpetrator(s), are nobody to you, and even if they were, you save your own hide and keep the distance, both physically and emotionally.

It’s the attitude of the era we are living in, and it’s contagious. In an overpopulated world, where we are teeming together with barely space to move and breathe, we feel alone, lonely, forsaken, and insecure, scared!

It’s an attitude we each have adopted that has seen the world degenerate into the selfish, me-first and only-me matters culture that we each crib about, but accept it as the ‘norm’ of today.

Our unspoken code of conduct has become, nobody cares about me, and neither do I care about what happens to them. I’ll exercise my rights going about doing my thing with my eyes glued to the ‘likes’ on my Instagram or Facebook and let the world go by as it is, since it’s not ‘my problem to solve’, but that other person, that somebody else, but that ‘someone’ ain’t ME!

A perfect summation of the callous, uncaring, indifferent, and unsympathetic attitude of the times is in the catchy song from Coolie No. 1 (1995), starring Govinda and Karisma Kapoor, “Main Toh Raste Se Ja Raha Tha”, in which there’s a stanza saying, “so your nani died, so what is it to me. I was on my way, eating bhelpuri and taking my girl around; so, what’s it to me?”