Community members weigh in.

By Amornrat Sidhu

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has made it seem like we’re living in the middle of a war. We’ve had curfews and lockdowns, not because of raining bullets, but an invisible enemy infiltrating dermis lines. We’ve postponed weddings, limited attendees at funerals, changed our education system, and so on. As times rapidly change, three facets of human nature have emerged that continue to dictate how we act in this ‘war’: obedience, anonymity, and personal responsibility. *studies below were inspired by events in WWII.

OBEDIENCE

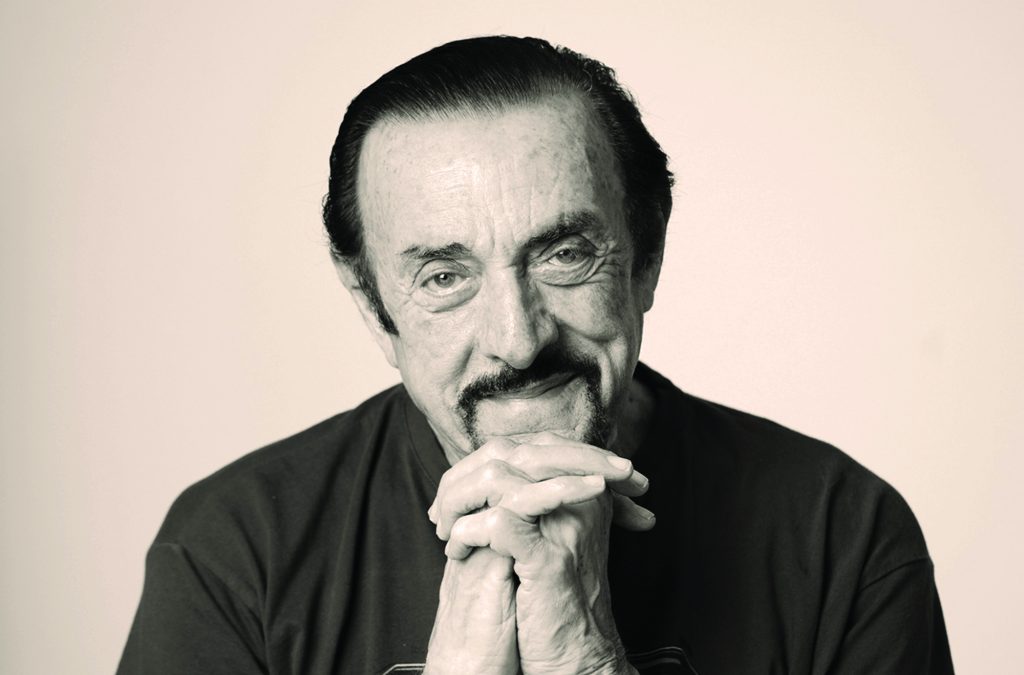

The most iconic study on obedience was conducted by Stanley Milgram in 1963, who wanted to explore why so many German soldiers obeyed Nazi orders to commit atrocious crimes. Through his research, he found that under the right circumstances, everyone is capable of committing the same atrocities.

THE EXPERIMENT

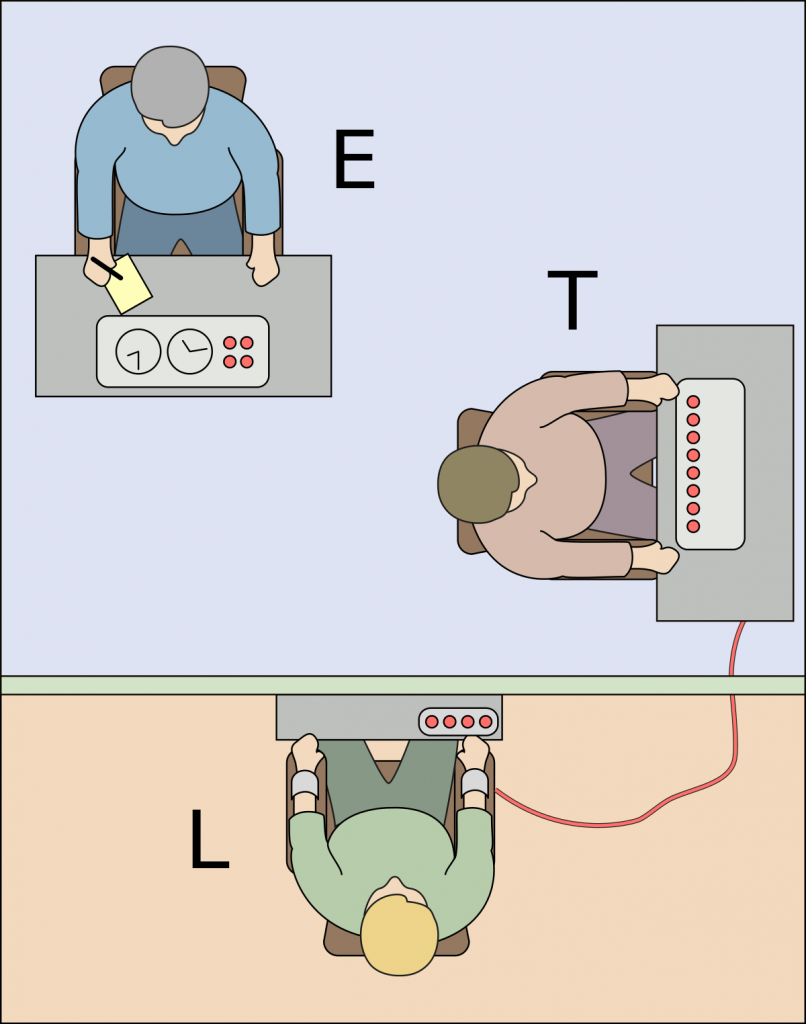

Milgram recruited male participants for an experiment conducted at Yale University. Each participant was paired with a ‘Mr Wallace’, who was actually a research assistant to the experiment, but the rest did not know this fact. The ‘Mr Wallace’ always picked a chit of paper that said ‘learner,’ while the other participants were always the ‘teacher’. As per the set-up, the teacher and an ‘experimenter’ (played by an actor) were in one room while ‘Mr Wallace’ was in another.

During the experiment, the teacher had to ask a question and give ‘Mr Wallace’ an electric shock of 180 volts using a manual shock generator each time he made a mistake. As the experiment went on, the voltage would increase every time he made an error or did not answer the question.

Although the participants could not see each other, the ‘teacher’ would hear ‘Mr Wallace’ scream from the pain, pound on the door, and beg for the teacher to stop at 300 volts. At 315 volts, they would hear silence from ‘Mr Wallace,’ hinting that he had either passed out or died. Despite the silence, the ‘experimenter,’ dressed in a lab coat, would urge the ‘teacher’ to continue by insisting that the experiment required it. The ‘teacher’ then felt pressure to carry on, giving electric shocks to ‘Mr Wallace’ even though he had stopped responding.

THE RESULTS

It is rumoured that Milgram believed that all Germans were made of a different, crueller skin. However, he found that ALL participants, regardless of who they were and where they came from, decided to continue shocking ‘Mr Wallace’ until 300 volts, and that 65 percent of participants shocked him until 450 volts. This was wildly different from his original hypothesis that predicted that less than 5 percent of the participants would go through with the experiment.

INTERPRETATION

The conditions were right to expect obedience.

Prestige– there was prestige involved as the study was conducted at Yale University and participants trusted that the experimenters would be ethical.

Monitoring– the presence of the authority figure was felt. The authority figure (the experimenter) was stood right beside the ‘teacher’ so it was difficult to refuse the orders, even under immense discomfort.

Authority– the authority figure looked the part. Each wore a lab coat and was professional in their demeanour.

Personal Responsibility– many of the participants shifted blame to the authority figure so they did not feel personally responsible for the pain they caused. In variations of the same study, when physical closeness was increased, participants became less likely to obey because they felt more responsible. For example, when the ‘teacher’ had to physically place ‘Mr Wallace’s’ arm onto a shock plate instead of administering the shock from a distance.

Barrier– There was a wall between the ‘teacher’ and ‘Mr Wallace’ so participants could not physically witness the pain they were causing.

HOW THIS APPLIES TO COVID-19 IN INDIA AND THAILAND

We have seen major differences in how Thailand and India have approached controlling the pandemic, and this is due in part to factors surrounding obedience and authority.

Awareness of Personal Responsibility

In Thailand, there seems to be more awareness of personal responsibility and the individual power one has to protect ourselves and others, which Milgram has demonstrated plays a huge part in influencing socially acceptable or ‘correct’ behaviour. In India, a country that still propagates an underlying ‘caste consciousness’, there remains a divide, a feeling ofdetachment to COVID-19, and an ‘it can’t touch me’ attitude.

Furthermore, it also helped that towards the end of last year, the majority of Thai people voluntarily donned masks to protect themselves from the pollution (another sign of personal responsibility) unlike the majority of urban Indians. This made it easier for Thais to accept wearing masks due to COVID-19.

Prestige and Monitoring

While corruption exists in both countries, authority figures such as police and frontline workers seem to be given higher esteem in Thailand than in India. It is arguable that there is less of a ‘talk your way out of anything’ attitude amongst Thai people when compared to Indians living in India. Don’t believe me? Just observe how Indians from India speak to salespeople in Siam Paragon compared to Thai-Indians. It’s often totally different!

“When the lockdown was announced in Thailand, everyone followed the protocols strictly—social distancing, masks, sanitisation, everything. However, in India, despite lockdown being announced before Thailand, social distancing was non-existent. Furthermore, the law in Thailand was that anyone who tested positive had to be hospitalised immediately, resulting in those with symptoms receiving the treatment they needed, and many making a recovery. However in India, partially because of the massive population, the healthcare system could not, and did not reach everyone equally.” – Paveena Rathour, Thai resident currently living in India.

“One of the reasons India’s cases continue to rise is because educated people in India are being ignorant about the pandemic. They are not following protocols because they are under the impression that their immunity is strong because of the pollution in India. Unfortunately, they are mistaken.” –Deepti Sharma, Indian citizen living in Delhi

DE-INDIVIDUATION AND ANONYMITY

Deindividuation is when you feel reduced accountability for your actions as a result of being in a crowd. This is very much connected to anonymity, when you cannot be identified, as this is more likely to happen in a large group of people.

The Experiment and Results

In one condition, the participants were made to wear lab coats and hoods that covered their faces so that they could remain anonymous and blend in with the group. It was found that these women behaved more aggressively towards the actors, choosing to administer stronger and longer electrical shocks.

This contrasted with a variation of the experiment where the women were forced to wear name tags and their own clothes, which found that they were kinder and administered less shocks.

Interpretation

It’s evident that the more likely you are to be identified, the more likely you are to feel responsible for your own actions and to follow rules. Whereas, the bigger the crowd, the more likely you are to blend in and lose your sense of self, which leads to you being more likely to break rules. This study lends a role in explaining cult behaviour, race riots, and football violence. This is why ‘peaceful activists’ sometimes turn aggressive during protests if the rest of the group becomes violent. This is also known as ‘mob mentality,’ where a person’s identity within a group overrides their personal identity and self-awareness.

HOW THIS APPLIES TO COVID-19 IN INDIA AND THAILAND

India’s recent history has been marked with sporadic race riots. Despite the threat of COVID-19, there has been constant threat of protests occurring at any time. If you cannot be identified because you are veiled by a crowd, it’s easy to find yourself going along with an ideology, or even blaming a group of people because others are doing so.

The recent news has depicted ‘Chinese-looking’ Indians, Muslims, and other racial and religious groups being targeted and attacked, and perhaps this violence is heightened because of the increased anonymity that masks provide.

In contrast, Thailand, which has dealt with its own share of political uncertainty, is generally quite peaceful and tolerant. While the scapegoat in the case of COVID-19 is the Chinese population and the tourists, the Thai- Chinese locals are still held with a lot of respect. This is different to their social standing in India, and perhaps why they have escaped the brunt of the misguided blame in their own country.

“I think the fear of COVID-19, coupled with the uneasiness of a lockdown, can make people lash out. If you did not know

how to feed your family the next day, or the next month, or were locked in the house to homeschool your three children, I think you’d begin to feel frustrated and may do unpredictable things, too. And do I think the anonymity that masks provide helps in spurring the violence, fear, and hate? Yes, I do.”- Anonymous, living in Mumbai

“A large section of the population is in the middle class, and they are particularly afraid of testing positive and being in isolation or hospitalised for long periods of time. Thus, they do not get tested and just stay home. The large population of India provides a blanket of anonymity, and because contact tracing is very difficult to do people think they will not be caught.” – Deepti Sharma, Indian citizen living in Delhi